Analysis

News

Publié le : 13/03/2023

The new Saudi deal

Cinzia Bianco, visiting fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, where she is working on political, security and economic developments in the Arabian Peninsula and Gulf region and relations with Europe, agreed to answer the Newsroom’s questions about the new Saudi deal.

Additionally, Cinzia is a senior analyst at Gulf State Analytics. Previously, Bianco was a research fellow for the European Commission’s project on EU-GCC relations ‘Sharaka’ between 2013 and 2014.

ghj

To begin with, what is your reading of the relationship between Saudi Arabia and Europe in general, in light of the changing Trump administration and the war in Ukraine?

Under the presidency of Donald Trump, Europeans suddenly found themselves butting heads with Washington on key regional files, including in the Gulf. Gulf monarchies saw their core covenant with the US betrayed as Trump failed to respond to the September 2019 Iranian attacks on Saudi Arabia’s ARAMCO oil facilities in Abqaiq and on international and Emirati tankers in UAE territorial waters. The deterioration of US credibility in the GCC – resulting from the Trump administration’s lack of commitment to regional security – provided Europeans with an opportunity to show the value of their partnerships. This continued under the presidency of Joe Biden, as it quickly became clear that declining US interest in the Middle East was structural in Washington DC.

This ongoing US retrenchment is the fundamental context to explain why Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf monarchies refused to side with the West as Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. In fact, Riyadh and the other Gulf capitals started an extreme strategic hedging that opportunistically maximised their own interests. They refused to adopt any of the Western sanctions on Russia and, in some cases, effectively provided ways for Russia to circumvent those sanctions. On the issue of energy, Riyadh continued to firmly seek coordination with Moscow, despite protestations from teh US and Europe. Saudi Arabia far resisted strong calls by Washington, London and Paris to push oil prices down by increasing outputs. At the same time, Riyadh voted with the US and Europe in every resolution against Russia at the United Nations. Declaring an aspiration of working as a mediator in the crisis, the Saudi leadership has also palyed a role in delivering some humanitarian aid to Ukraine and facilitating a prisoners exchange between the two sides.

Europeans have been slow and confused in acknowledging these simoultaneoud dynamics, i.e. a US retrenchment from the MENA region, combined with a growing role of Russia and China, a greater self-confidence by regional actors, with the emergence of Arab Gulf leadership in the wider region. However, a reckoning has been underway in Europe, especially accelerated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and its wider implications on European energy security.

“There is a clear opportunity in Europe-Gulf cooperation on innovative energy relations and cooperation on the energy-climate nexus.”

rtyu

While Europeans are concerned about the geopolitical and military implications of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Europe is already paying a high price in two other domains: energy and economy. This creates the context for Europe to seek a strategic energy partnership with Gulf producers, not as a temporary tactics against Russia, but as a first step in a long-term engagement, geared towards smoothening the energy transition for both sides as well minimizing the shared risks of energy insecurity. Indeed, the enaggement between European and Saudi actors since 2022 has been orders of magnitude more intense than in the previous years. Senior policy-makers from Germany, France, Italy, the European Union and beyond have paved visits to Riyadh, working to relaunch comprehensive relations that look at energy security as well as the green transition, climate, trade, investment and even a closer geopolitical dialogue and people-to-people or cultural relations. There is a clear opportunity in Europe-Gulf cooperation on innovative energy relations including the decarbonisation of the energy industry, the development of green energy relations – such as hydrogen – and cooperation on the energy-climate nexus. These have implications for other areas as well, such as trade and investment, scientific and technological cooperation and, even, convergence of interests in maritime security around the region.

A realization that the Gulf was growing more relevant for European core interests encouraged the negotiation of new Cooperation Arrangements between the European Union (EU) and every Gulf Cooperation Council country over the past few years. Similarly, it encouraged the EU and the GCC to work on a new EU-GCC Joint Cooperation Programme (JCP), and publish comprehensive document titled “A strategic partnership with the Gulf” in 2022 of which energy is only one out of several domains.

This recent acceleration builds on a few years of closer relations. In 2021, Saudi Arabia signed a Cooperation Arrangement with the EU. Saudi Arabia opened its mission to the EU in 2018, specifically to advance cooperation linked to Vision 2030, including economic diversification, education and the energy transition.[i] These are the same domains of focus for the Cooperation Arrangement. The EU instead opened its delegation to the Kingdom already in 2004, recognising Saudi Arabia’s weight as a global financial player, its political influence in the Gulf, the wider MENA region, the Red Sea and its soft power influence in the Islamic world.

[i] Saad Bin Mohammed al-Arify. “EU and Saudi Arabia: Common challenges, joint efforts, shared goals”, Euractiv, 15 July 2020. https://www.euractiv.com/section/global-europe/opinion/eu-and-saudi-arabia-common-challenges-joint-efforts-shared-goals/

We know that the Abu Dhabi – Riyadh axis has long given the foreign policy of the Gulf States in the region, and even beyond if we consider the other major Sunni countries such as Morocco, Egypt or Jordan. In your opinion, will this double entente withstand the Saudi temptation and especially that of MbS to take the regional leadership?

After almost a decade of fully working in team in regional geopolitics, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are probably going to work more and more independently from one another. The UAE, with all the due differences in geopolitical weight, is effectively the only other regional actor that has the strategic capability of pursuing alternative courses and conflicting interests. It is perhaps for this reason that the years-old idyllic relationship between the two strong leaders, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman (MbS) and Emirati President Mohammad bin Zayed (MbZ), is now going through some turbulence.

There were divergences of views and interests between MbS and MbZ at least since 2018. Saudi Arabia and the UAE both wish to extricate themselves from the costly war in Yemen pronto, but Abu Dhabi has shown willingness to do this unilaterally, focusing on its allies in the south of the country, to secure continued access to strategic coastal infrastructures. Saudi Arabia’s reforms to attract foreign direct investment – such as the HQ law, stipulating that to do business with the government, firms should have their MENA HQs in Saudi Arabia – are a significant challenge to Dubai and the UAE. MbZ, also thanks to the normalization of relations with Israel, is in a completely different political spot in Washington D.C. and has repeatedly questioned MbS’ bold challenges to US redlines, such as on oil production quotas, that are the product of the specific acrimony there.

“The two leaders, who used to speak frequently with one another over the phone, are no longer that much in contact”

sdfg

The UAE also opposes the restoration of maximum pressure on Iran, while Riyadh would want to see coearcive diplomacy towards Tehran. MbZ did not attend the high-level summits with the Chinese president Xi Jinping in Riyadh in December 2022. MbS did not attend a recent summit hosted by the UAE and including Egypt, Jordan and Qatar. The two leaders, who used to speak frequently with one another over the phone, are no longer that much in contact. If some form of MbZ’s mentoring of MbS existed in the past, as Riyadh was certainly inspired by the UAE on reforms, this seems to no longer be the case. If divergences between Saudi Arabia and the UAE long existed, they were kept very much below the radar by the political partnership at the top. The fact that this partnership is now weaker, means that the old divergences can emerge more strongly, too.

These Saudi-Emirati tensions don’t necessarily have to turn into active confrontation and – in fact – the capability of containing divergences with Abu Dhabi, Cairo or any other capital in the region – from spilling into proper hostility would likely be one of the factors determining the strategic maturity needed to achieve regional leadership. But the Saudi-Emirati honeymoon with the UAE is over and, while agreeing on the basic objectives, the two actors now have different visions for the region.

The Qatar World Cup reinforced MbS’s belief that only the opening up of the country, its economy and its cultural renaissance could help the Kingdom compete with other powers in terms of soft power. Vision 2030 is the foundation of this unprecedented transition. In your opinion, will the Crown Prince be able to deal with the Kingdom’s conservative forces to carry out structural reforms?

Over the past few years, Saudi Arabia has been constantly re-positioning, domestically as well as internationally. The input to change has come from Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman (known as MbS), the youngest leader in the country’s recent history. MbS presented himself as the regime’s best hope to bridge a growing gap between an aging leadership and an exceptionally young population, where over half of citizens are under 30 years old, in the post-Arab Spring era. Re-imagining a version of the ultra-conservative Kingdom to the liking of the Saudi youth, without questioning the deeply autocratic political system, has led to a number of contradictory policies. Domestically, while the economy and society have been swept by an unprecedented liberalization process, politics has become even more illiberal and repression of dissent more forceful. Internationally, the urge to push Saudi Arabia to become a regional leader has both resulted in the acceptance of greater responsibility towards regional security and in aggressive policies such as the war in Yemen.

“The Saudi leadership clearly sees megaprojects as catalysts to spearhead all of this growth.”

erg

Vision 2030’s main goals for the Saudi economy are to boost the private sector, increase the share of Saudi nationals in the private workforce and diversify away from overreliance on the fossil fuels industry. In this regard, the government has been pushing to diversify the economy betting on sectors like tourism, logistics, renewable energy, entertainment, real estate, finance and high-tech, significantly simplifying and incentivizing investments (especially foreign) in those domains. The Saudi leadership clearly sees megaprojects as catalysts to spearhead all of this growth. These include the futuristic mega-city of NEOM and zero-carbon development The Line, the touristic sites of Al-Ula, Amaala and The Red Sea Project, Diriyah Gate and the Qiddiya entertainment village, as well as the mega-industrial complex on the Red Sea, Oxagon.

By the same token, the Saudi leadership has come to see mega-events as further catalysts. This explains Riyadh’s strong and strategic interests in hosting either the World Cup or EXPO in 2030. This would also be the Vision’s deadline eyar, making the mega-event even more important.

Since 2016 experts have wondered whetehr MbS and the Saudi leadership would manage to push ahead with modernization, amid a very conservative Saudi society. In fact, between cooptation and hash coercion, the Saudi leadership has gone ahead and directly against the interests of conservatives, massively cracking down on their networks and resources. While a backlash is still technically possible, it is certain that the leadership has worked to prevent this and keep the oppositin tightly under control.

Iran no longer hides its regional hegemony and de-escalation efforts in the Persian Gulf and the Middle East remain uncertain and fragile. In your opinion, how can Europeans play a role in promoting cooperation between the Gulf States and in dissipating Iranian ambitions? Can this be done through dialogue around a challenge common to all these countries, such as the climate challenge?

Iran’s brutal repression of protests in 2022 and Iran’s military alliance with Russia in its invasion of Ukraine have significantly changed Europe’s perspectives on the Islamic Republic. The talks on revamping the nuclear dealhave now collpased and Europeans, who have been the loudest voice to support them, have no intention of trying to support them any longer. Europe and the Gulf monarchies are, after years, on the same page when looking at Iranian drones and ballistic missiles as a core security threat.

“There is an urgent need for a new platform on which to maintain dialogue : a platform that centres on climate and environmental security may be the only politically feasible option.”

qsdfgh

At the same time, this new situations could also close some channels of regional diplomacy and raise the level of threat and insecurity for the Gulf monarchies. The United States has already started pressing Gulf monarchies to reduce some of their economic engagement with Tehran, by imposing sanctions on Emirati firms for trading Iranian oil. In doing so, the US is depriving Gulf states of the incentives they can offer to Iran in return for de-escalation. In this context, there is an urgent need for a new platform on which to maintain dialogue. A platform that centres on climate and environmental security may be the only politically feasible option and external support might help insulate the process from political shifts in the region.

Traditionally, environmental security has not driven policy in the Middle East, where regimes’ highest priority is political security. But the link between the two areas is becoming clearer. This is especially so in Iraq and Iran – where there are growing public protests about water scarcity and the impact of pollution on public health, and where climate-induced migration is becoming a challenge. Hosting ministerial representatives from 11 states at a July 2022 conference on “Environmental Cooperation for a Better Future”, Iran showed interest in using environemntal security as a platform for de-escalation. Both Iran and Iraq see the benefits of cooperating with wealthier and more technologically advanced Gulf monarchies. Gulf monarchies, which are better equipped to cope with environmental degradation, still recognise the political value of international climate politics, and have overseen initiatives and investments in this area. For instance, Saudi Arabia launched the Middle East Green Initiative, and the UAE will host the 2023 United Nations’ Conference of the Parties (COP28). Gulf monarchies also want to maintain channels of communication with their neighbours in a tense and unstable geopolitical environment, and to strengthen regional initiatives in response to their decreasing trust in actors further afield.

“France, given its hosting of the Baghdad Conference for Cooperation and Partnership should have a leading involvement.”

fghj

Europeans should work to reinforce regionally owned diplomatic processes that have developed in the past year, especially by linking disparate initiatives and prioritising consistency and the establishment of a coherent, sustainable, and practical dialogue. France, given its hosting of the Baghdad Conference for Cooperation and Partnership should have a leading involvement. The main topics for such a diplomatic event should be: water sharing (especially with Iraq); coordination on natural disaster relief; the expansion of Saudi Arabia’s afforestation plans under the Middle East Green Initiative to Iraq and Iran; and political backing for enhanced scientific and technical cooperation between non-governmental bodies. COP28, hosted in 2023 by the UAE, would provide the perfect setting. Indeed, the four key Middle Eastern actors in climate diplomacy – Iran, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and the UAE– have shaped their environmental diplomacy around UN events or initiatives, such as COPs.

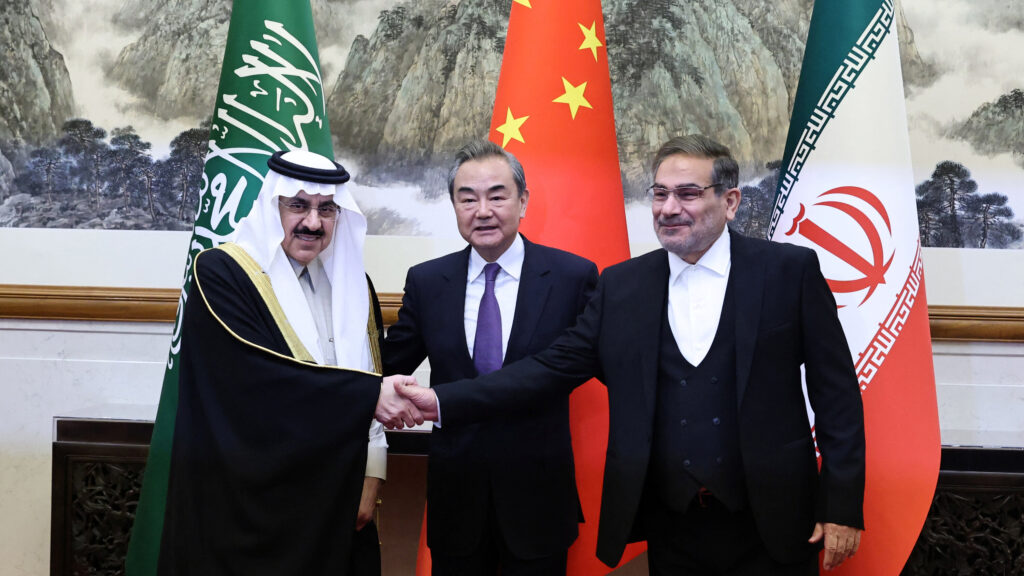

How do you read this Chinese diplomatic breakthrough on the Iranian-Saudi issue?

The deal signed on March 10 between Iran and Saudi Arabia is a roadmap to restoring diplomatic relations between the two rivals after 7 years of complete estrangement. This is a good development for the region, which suffered the deeply destabilising consequences of the Saudi-Iranian rivalry. The fact that a deal has now been reached suggests that the two sides have made some progress in addressing critical areas of dispute such as, for example, Yemen.

“Saudi Arabia views this agreement more as a hedging bet to protect it against Iranian attacks, than as a meaningful strategic realignment.”

frghjk

Still, moving from this initial agreement towards meaningful regional stability will be a long journey given the deep distrust and fundamental geopolitical opposition between these two states. Saudi Arabia views this agreement more as a hedging bet to protect it against Iranian attacks, than as a meaningful strategic realignment. At the same time, Riyadh has also been exploring enhanced ties with Israel to cement a regional anti-Iran front. And yet, as opposed to Israel’s desired confrontation stance – the Gulf monarchies view engagement as necessary as containment to deal with Iran. This is all part of the extreme hedging and strategic ambiguity now embraced, on all fronts, by Saudi Arabia.

It also very noticeable that the agreement was signed in Beijing, as China pushed it through the finish line. However, this agreement was built on years-long secret talks hosted by Iraq, Oman and France, via the Baghdad Conference for Cooperation and Partnership. Likewise, the contribution of regional and European actors will still be needed to build on this fragile agreement, trying to make it more sustainable and resilient to political ups and downs. In particular, Europeans should re-energize existing dialogue tracks on maritime security (via the French-led mission EMASoH) and the very promising potential for dialogue on environmental security, (https://ecfr.eu/publication/a-new-climate-for-peace-how-europe-can-promote-environmental-cooperation-between-the-gulf-arab-states-and-iran/#recommendations) ahead of COP28, hosted by the UAE later this year.

Last month, Saudi Arabia celebrated “Founding Day” for the second time in its history, in reference to the takeover of the town of Dariya by Imam Mohammad bin Saud in 1727. An occasion to remind us that Saudi Arabia is no longer just a ruling family but a nation-state?

The Founding Day was introduced by the Saudi leadership in 2022 to celebrate the beginning of the reign of Mohammed ibn Saud and the foundation of the first Saudi state in Diriyah on 22 February 1727. This choice has substantial political significance as it introduces a new – and, perhaps – more important day to celebrate the political identity of Saudi Arabia. In fact, this new holiday informally replaces 23 September 1744, the day cleric Muhammed ibn Abdul-Wahhab and ruler Mohammed ibn Saud made a covenant to establish together the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Until 2022, this was the only national day, a very powerful symbol of the link between the state and Wahhabbism.

“The introduction of Founding Day is therefore a radical break with the Wahhabi political influence that had legitimized the Saudi political project so far.”

gh

The introduction of Founding Day is therefore a radical break with the Wahhabi political influence that had legitimized the Saudi political project so far. By choosing 1727 as the new official founding year, MbS moved the focus away from the covenant with the Islamic clergy and Muhammad ibn Wahhab in order to “divorce” the founding of the Kingdom from anything associated with Wahhabi influences. By selecting the beginning of the reign of Mohammed ibn Saud as the state’s foundational moment, it creates a new myth that leaves no room for Muhammed ibn Abdul-Wahhab and his movement.

This year’s Founding Day was marked by celebrations all around the Kingdom, including displays, music and historical representations that also celebrate the pre-Islamic time of Saudi Arabia. But this year’s Founding Day was mostly important for the decision taken by the Saudi leadership to build on it by establishing another celebration, Flag Day, on March 11. Traditionally, Saudi Arabia’s flag evokes a sense of devotion and loyalty to Islam, as its green color and white inscription of the Shahadah (the Muslim profession of faith) symbolise. However, already last year the Saudi leadership initiated a national debate on tweaking and modernising the flag, to represent a new Saudi Arabia where Islam is certainly part of the identity but not the exclusive reading key of the Kingdom.