Analysis

Analysis

Publié le : 25/07/2025

Building Public Interest AI : Perspectives for Morocco and Africa

Martin Tisné, Founder and Chair of the Board of Current AI*, shares with the Newsroom his vision for ethical and inclusive artificial intelligence. At the intersection of technological sovereignty and purpose-driven innovation, he outlines the conditions for building public-interest AI across Africa—and calls for governance rooted in the real needs of communities.

*Current AI is an innovative global partnership launched in Paris last February during the Summit on AI Action, aimed at harnessing artificial intelligence for the public good.

You launched Collaborative AI with an initial fund of $400 million, aiming for $2.5 billion to finance public-interest AI. How can countries like Morocco build local capacity while participating in global ecosystems? And what lessons can be learned from your experience with the Open Government Partnership to ensure ethical, inclusive, and truly participatory governance of AI in Africa?

It starts and ends with asking, listening, and understanding. What do people and communities want and need from AI? What does society look like when AI is working for them, with them?

This approach can help countries like Morocco to build three components that are indispensable for Public Interest AI to thrive – better data, truly open AI ecosystems, and accountability to people and communities, which means having a concrete and evidence-based grasp of the impact of AI on society, being transparent about it, and making and justifying decisions accordingly. Global ecosystems have been lacking in this respect so far; in this context, building local capacity that centers people and communities can help countries go beyond participating in global ecosystems, to shaping them as they bring unique perspectives and added value.

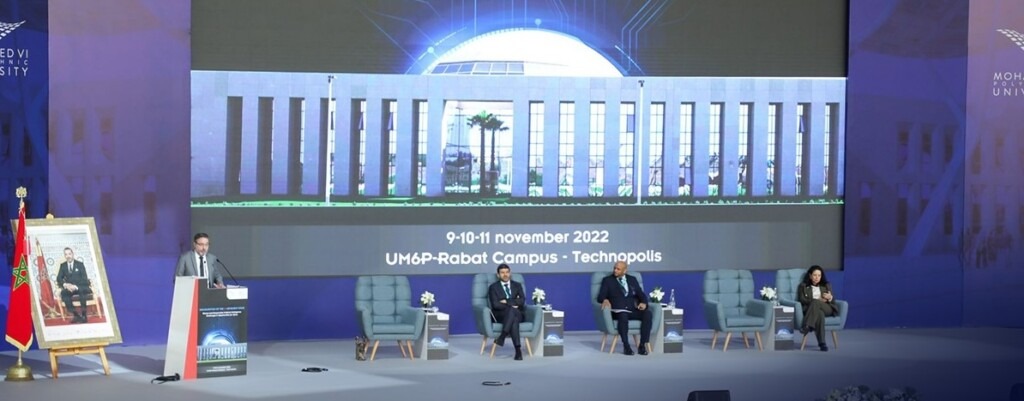

Morocco is making crucial contributions to the future of AI across Africa and the Arab world, showcasing national ambition and a long-term commitment to building AI systems and tools that serve the public interest and are rooted in local values, priorities, languages, and history. Mohammed VI Polytechnic University’s AI Movement Centre’s remarkable work – using AI to recognise Arab dialects and advancing research in neuroscience and mental health – exemplifies this.

Martin Tisné alongside the co-founder of MGH Partners in Rabat, on the sidelines of the first National Conference on AI – July 2025.

The critical Open Government Partnership [OGP] experience is really this closeness in working between and across stakeholder groups. When we started OGP back in 2010, from the get-go the Steering Committee was composed of 50-50 government officials and civil society, which enabled us to unlock new innovations and experiences. A second critical experience is closeness to the ground, having started at the national level OGP then launched “OGP local” and partnered with cities around the world on open government reforms. I am excited about both possibilities.

From 9th to 11th November, the Ai movement Center of Mohammed VI Polytechnic University launched the Ai Dome, at UM6P campus in Technopolis, Rabat.

You often speak about the importance of collective data rights to better protect communities, beyond individual rights. How can these rights be concretely implemented in African countries where citizens share their data on a massive scale, often without real information or democratic consent? What preconditions are necessary ?

We need to find the balance between individual privacy rights and the opportunities (and threats) presented by collective data usage. The first precondition is to know what the unit of analysis is, what the ‘collective’ we are talking about is – are these the patients within a given hospital? The parents within a given school? People suffering from the same disease? Let’s start very concrete with these case studies and then build up. It’s both a question of protecting communities and of enabling them to take advantage of that data. These are a number of different approaches to data stewardship that are relevant from data trusts, to data cooperatives.

Johannesburg © Sopotnicki

In a context where Africa, and particularly Morocco, is seeking to attract private investment to build its AI ecosystem, how can we reconcile the logic of public interest and economic attractiveness? And on the question of infrastructure: should we prioritize technological sovereignty (national clouds) or accept a certain dependence for greater agility and efficiency?

Let’s question the premise that public interest and economic attractiveness are estranged in the first place. Value creation and delivery are at the heart of both theory and practice in the world of management, entrepreneurship, and business, even if not all actors subscribe to this approach and many adopt it only as rhetoric. So, perhaps, it is not a matter of reconciling public interest and economic attractiveness, but championing and funding the builders and innovators who build with purpose and seek profit as a crucial outcome but not the main goal, aiming to solve pressing problems to deliver value to people.

At the same time, we need to recognize that markets are imperfect and oftentimes are not optimized to incentivize the creation and delivery of public value. This is an obstacle, but not an insurmountable one. Building AI with a public purpose at the center can deliver meaningful societal outcomes alongside technological breakthroughs, leading to more resilient, relevant, and future-ready innovation. A public interest-based approach can help nations and innovators balance long-term societal benefits with national interests, economic competitiveness, and technological leadership—demonstrating that at their best these goals are mutually reinforcing. So, in practice, we need to enable these kinds of builders and innovators, so their cases can become the evidence that shows that social and economic outcomes go hand in hand. In so doing, sovereignty is critical in so far as it empowers local innovation ecosystems. What matters is delivering to people long term.

Data centers © Google

You contributed to the Digital Republic law in France, which advocates for algorithmic transparency. How can these principles be adapted to African countries that still lack the technical capacity to audit and understand complex systems? Isn’t there a risk of excluding these countries from international standards due to a lack of resources?

The Digital Republic law is a French national law that does not inherently set international standards and primarily enshrines algorithmic transparency related specifically to automated decision making in the French public sector.

The mistake to avoid is for the State to contract with private sector vendors whose technology it may not understand and then won’t be able to audit.

So at its core, this is a matter of public sector capacity and a challenge for any and all countries.

One of the emblematic cases that exemplifies this mistake is the use of the MiDAS system in Michigan, USA. This system was used to determine if a given person committed fraud in applying to unemployment benefits. The system was wrong more than 90% of the time and it mistakenly flagged approximately 40,000 cases as fraud. Ultimately if any country, in Africa or another region, is at a stage where it’s comfortable using these systems for automated decision making, it should understand them and feel comfortable auditing them.

Emmanuel Macron speaks during the plenary session of the Summit on AI Action, in Paris, on February 11, 2025. (LUDOVIC MARIN / AFP)